- Home

- Wetland Site

- Tunis Lake, Tunisia

Tunis Lake, Tunisia

Tunis Lake forms the southern part of the Gulf of Tunis and was formed in the 11th century AD. Although the lake is a separate basin due to silting and disconnected from the sea, it is not disconnected from its environment and is affected by multiple factors. The lagoon has been divided into Northern and Southern lakes since the French dredged a navigation canal in 1881 to allow boats to enter Tunis harbour. The lake provides food for more than 100 bird species that winter in the lake, as well as for the yellow-legged gulls and egrets that nest there. Commercial fisheries operating in the lake produce up to 500 tonnes a year. The lake has been seriously degraded during the 20th century as a result of modern urban development. It is a Ramsar site and an IUCN category IV natural reserve. As a wetland of national importance (category VIII), it is protected by the Forestry code and has been a natural reserve since 1993.

Settlements and structures (ancient/traditional/modern)

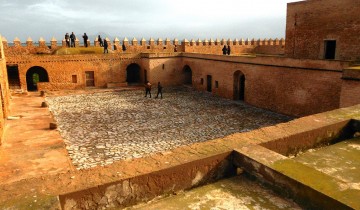

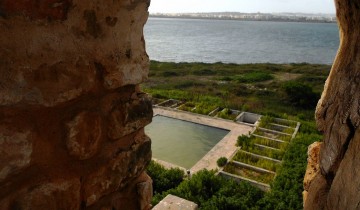

In the 2nd century BC, when the lake was still open to the sea, it was the site of a Carthaginian port whose remains are still visible today. Chikly Fort, built on the island of Chikly, was initially constructed by the Aghlabids between 800 and 900 AD and later abandoned. The Spanish re-built it in the 16th century as part of the city defences and renamed it ‘Santiago Fort’. The fort was restored in the 1990s. Ceramics, coins and brightly-coloured mosaics from the Roman and Byzantine periods have also been discovered at the site. The lakes’ cultural interest is also linked to their proximity to the Medina of Tunis, a UNESCO World Heritage Site enclosed by the modern city of Tunis. The Medina includes approximately 700 monuments—palaces, mosques, mausoleums, etc.—dating from the Almohad and Hafsid eras (13th-16th centuries AD).

Water use

Littering, eutrophication, domestic wastewater, industrial runoff, poor drainage, population growth and urban development have all compromised the site in the 20th century. Traditional fishing and hunting have also been abandoned and there is little documentation in existence. In the second half of the 20th century, clean-up operations were carried out in the context of large residential urbanisation programmes and the water circulation improved significantly. At the same time, though, the lakeshores were reclaimed, the city expanded, and both natural habitat and cultural values were endangered. However, we can see the results today of the large-scale sanitation programmes that have been undertaken, both in the much improved water quality and the progressive recovery of the lake’s ecological functions.

Scientific research and education

In an effort to reconnect the cultural aspects of the site with the natural habitat, the stakeholders responsible for its protection—a number of NGOs and environmental institutions and administrations—have ascribed to the idea of a Centre for Ecological and Cultural Interpretation of Lake Tunis opposite the nature reserve on the island of Chikly. The Centre’s role will be to present the site of Chikly to the public, communicating its historical and cultural significance, the ecological fragility of its environment and the need to protect this culture, history and ecology.